ISFAR Critique #289 – Effect of moderate alcohol intake on blood apolipoproteins concentrations: A meta-analysis of human intervention studies – 14 March 2025

Authors

Khatiwada, A., Christensen, S.H., Rawal, A., Dragsted, L.O., Berg-Beckhoff, G., Wilkens, T.L.

Citation

Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2025; Jan 3:103854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2025.103854.

Author’s Abstract

Background This study assessed the effect of alcohol intake (up to 40 g/d) on blood apolipoproteins (APOs) concentration in human intervention studies. Additionally, it evaluates whether the effect of alcohol intake on APOs differs depending on sex.

Methods The literature search was performed in PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and Web of Science databases. The Cochrane risk of bias tool was applied. A total of 5559 articles were identified, yielding 80 articles for full-text screening. Twenty-five articles were included for data extraction.

Results Compared to no alcohol intake, alcohol intake up to a dose of 40 g/d showed an increase in Apolipoprotein A-I levels (ApoA-I) [mean difference (MD): 7.77 mg/dl, 95 % confidence interval (CI): 4.95 mg/dl, 10.59 mg/dl] and Apolipoprotein A-II levels (ApoA-II) [MD: 1.61 mg/dl, 95 % CI: 0.33 mg/dl, 2.90 mg/dl], but no significant change in Apolipoprotein B levels (ApoB) [MD: – 0.06 mg/dl, 95 % CI: – 3.38 mg/dl, 3.27 mg/dl]. Males showed a significant increase, while females showed a non-significant increase in ApoA-I levels [MD: 9.70 mg/dl, 95 % CI: 6.16 mg/dl, 13.28 mg/dl vs MD: 7.31 mg/dl, 95 % CI: – 0.67 mg/dl, 15.30 mg/dl]. The results had less certainty as most studies were at high risk of bias.

Conclusion Alcohol consumption up to 40 g/d increases ApoA-I and ApoA-II levels. Further research is required for ApoB. Considerations should be given when applying this research to practice. High-quality clinical trials with large sample sizes and longer intervention periods are required, focusing on including female participants.

Forum Summary

This meta-analysis by Khatiwada et al. (2025) is important since it evaluates the effects of moderate alcohol consumption on one of the mechanistic pathways involved in developing cardiovascular disease, namely lipoprotein metabolism. The authors conclude that alcohol consumption up to 40 grams per day increases apolipoprotein A-I and apolipoprotein A-II levels, whereas further research is needed for apolipoprotein B. Apolipoprotein A-I is the main constituent of the lipoprotein HDL, which transports cholesterol from lipid-laden macrophages of atherosclerotic arteries to the liver for secretion into the bile.

This type of information may further establish the mechanisms underlying the protective effect of moderate drinking on cardiovascular disease. Other epidemiological studies have indicated that apolipoprotein A-I increase is one of the most important contributors to the protective effect of moderate drinking on cardiovascular disease.

Forum members point out that the present paper is based on results of clinical trials. Thus, there is no reason to worry about ‘under-reporting’ or other misclassification of alcohol exposure (sick quitters or former drinkers) that may occur when estimates are based only on self-reported consumption as in epidemiological studies. The authors considered all pooled results of ´low´ or ´very low´ quality, which was primarily caused by the absence of very specific information in the analysed papers. Forum members strongly believe, however, that the apolipoprotein A-I increase is a real effect due to the large consistency in clinical and epidemiological studies. Forum members also believe that the results are valid for men and women, although the level of significance is less for women as for men. Apolipoprotein A-I and its lipoprotein HDL are pivotal in cardiovascular disease protection but may also play an important role in other chronic diseases like diabetes type II and other diseases.

Forum comments

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a chronic disease contributing to global mortality and morbidity. In many Western World countries, CVD is the main cause of death for middle-aged and older individuals (GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators, 2020). CVD is also a disease that may be prevented by adjusting lifestyle (Magnussen et al., 2023). Non-smoking, being physically active, maintaining a healthy body weight, and maintaining a healthy dietary pattern may prevent a considerable portion of CVD deaths (Zhang et al., 2021).

A long-lasting discussion exists on the role that moderate alcohol consumption may play. A vast body of epidemiological data suggests that moderate alcohol consumption is associated with a reduced incidence of CVD morbidity and mortality (e.g., Ding et al., 2021). Some studies even suggest that moderate alcohol consumption on top of a healthy lifestyle further reduces the risk of myocardial infarction in US men (Mukamal et al., 2006).

It is, however, important to understand what the mechanism may be underlying the epidemiological association between moderate alcohol consumption and CVD. A well-described mechanism will further substantiate an epidemiological association showing cause and effect. In the case of moderate alcohol consumption and CVD, various mechanistic pathways have been suggested and researched (Brien et al., 2011). Mechanistic research has been performed in various ways, such as using pathway indicators or biomarkers as a covariate in epidemiological studies or studying biomarker changes in controlled nutrition intervention studies. Biomarker changes have been incorporated as association-modifying parameters in epidemiological studies, and it has been shown that some biomarkers may be more relevant than others.

Rimm et al. (1996) observed that there was a significant dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and the plasma concentration of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), and its primary constituent apolipoprotein A-I, which was not significant for the other lipid biomarkers. HDL transports cholesterol from lipid-laden macrophages of atherosclerotic arteries to the liver for secretion into the bile, referred to as reverse cholesterol transport. HDL is also involved in inhibiting oxidation, inflammation, activation of the endothelium, coagulation, and platelet aggregation associated with atherosclerosis leading to coronary heart disease and peripheral artery disease (Chambless et al. 1997). In addition, HDL inhibits certain changes associated with the oxidative modification of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) by endothelial and smooth muscle cells (Durrington 1993, Klimov et al. 1993, Mackness et al. 1993). Therefore, a low plasma concentration of HDL and its constituents is a risk factor for CVD. Studies comparing the effects of beer, wine and spirit consumption on the plasma concentration of lipids observed that they all increased the plasma concentration of HDL (Parker et al. 1996, Ruideavte et al. 2002, de Jong et al. 2008), suggesting that this is an alcohol-associated cardioprotective biological mechanism. Alcohol increases the plasma concentration of HDL by stimulating the hepatic synthesis and secretion of its subcomponents, apolipoproteins A-I and A-II (Branchi et al. 1997, Sierksma et al. 2002).

Consequently, a meta-analysis of 42 experimental studies by Rimm et al. (1999), which examined the effects of alcohol consumption on CVD biomarkers, attributed the cardioprotective effect of light-to-moderate alcohol consumption: 60% to HDL-cholesterol, 20-30% to fibrinogen, 5-10% to insulin and 0-5% to other haemostatic factors. The meta-analysis also estimated that 30 g of alcohol per day would increase the plasma concentration of HDL by approximately 4 mg/dL, which would be associated with a 17% reduction in risk of coronary heart disease. It would also decrease the plasma concentration of fibrinogen by approximately 0.075 g/L, which would be associated with a 12.5% reduction in risk of coronary heart disease (Hines and Rimm 2001). This translated into an overall 24.7% reduction in the risk of coronary heart disease from the consumption of 30 g of alcohol per day. Klatsky and Udaltsova (2007) further translated this into a 10% reduction in risk of all-cause mortality.

A subsequent study by Mukamal et al. (2005) also suggested that up to 75% of the beneficial moderate alcohol consumption-CVD association could be explained by changes in the biomarkers HDL (increase), fibrinogen (decrease) and HbA1c (decrease).

Nutrition intervention studies have compared alcohol consumption with consuming a control beverage and have shown multiple changes in biomarkers, like those for lipoprotein metabolism, haemostasis, glucose homeostasis, inflammation and antioxidant status. Nutrition intervention studies, however, vary in design, in- and exclusion criteria, and statistical and analytical methods. Consequently, this meta-analysis by Khatiwada et al. (2025) is important since it evaluates the effects of moderate alcohol consumption on one of the mechanistic pathways, namely lipoprotein metabolism. This type of information may further establish the mechanisms underlying the protective effect of moderate drinking on CVD.

The authors conclude that alcohol consumption up to 40 g/day increases ApoA-I and ApoA-II levels, whereas further research is needed for ApoB.

Critique

This meta-analysis by Khatiwada et al. (2025) is a follow-up of various other reviews and meta-analyses. Rimm et al. (1999) arrived at similar results on ApoA-I as did Huang et al. (2017) and Spaggiari et al. (2020). Although other studies included other parameters not related to lipoprotein metabolism such as haemostatic factors and flow-mediated dilatation, Khatiwada et al. (2025) also analysed Apo A-II and Apo-B, studied gender differences and graded the certainty of evidence for each nutrition intervention.

Fortunately, results on Apo A-I from the various meta-analyses are quite consistent, only minor differences were observed in the magnitude of the changes. This may be surprising since the studies selected by Khatiwada et al. (2025) and others vary in numerous design aspects, such as length of intervention, dietary control, alcohol dosage, analytical methods and participant selection criteria.

A consistency in ApoA-I increase resulting from moderate alcohol consumption is relevant since ApoA-I, the major protein component of HDL, is considered to play an important role in many of the antiatherogenic functions of HDL (Stoekenbroek et al., 2015). These functions include reverse cholesterol transport and anti-inflammatory effects. Unfortunately, there is little discussion on how the results of this study by Khatiwada et al. (2025) may be translated into functional aspects and relevance to the moderate alcohol consumption – CVD association. Some of the authors of Khatiwada et al. (2025) did additionally analyse ApoA-I containing HDL subfractions and their functionality (Wilkens et al., 2022). They concluded that cholesterol efflux capacity and paraoxonase activity were consistently increased. Therefore, Wilkens et al. (2022) proposed that alcohol up to 60 g/day can cause changes in lipoprotein subfractions and related mechanisms that could influence cardiovascular health. Khatawadi et al. (2025) chose to remark, however, that caution should be applied when applying this evidence to practice.

The studies selected by Khatawadi et al. (2025) also provided little opportunity to compare genders due to limited numbers of studies available. This may be less of an issue for ApoA-I as compared to ApoB, since HDL (containing ApoA-I) is increased after moderate alcohol consumption in men as well as in women. However, there may be a clear difference for women depending on their postmenopausal status. Since CVD incidence rises sharply in women after menopause (El Khoudary et al., 2020), which is accompanied by distinct changes in lipoproteins (Wu et al., 2023). Therefore, subdividing studies in women, who were either postmenopausal or premenopausal, may have a substantial effect on the ApoB changes induced by moderate alcohol consumption. Other authors have suggested that ApoB may be reduced in moderately drinking premenopausal women (Clevidence et al., 1995), but hardly in moderately drinking postmenopausal women (Baer et al., 2002).

Furthermore, the meta-analysis of Khatiwada et al. (2025) suggests large bias in the clinical trials, although the effects of this bias may be overestimated overall. Bias was considered present when, in the randomization domain, details were incomplete or missing. Also, when information was lacking on wash-out periods in cross-over studies and carry-over effects, analyses were categorized as ‘high risk’ for bias. So, when authors did not include information in their papers on, for instance, randomization in a cross-over design, possibly due to restrictions of space or restrictions imposed by reviewers or journal editors, the risk of bias would increase from ‘low risk’, which was the best achievable level, to ‘some concern’ or ‘high risk’. Specifically in the case of cross-over designs, risk for randomization effects is extremely small, for example, since all participants receive all treatments. Similarly, period effects will not exist when the cross-over design is balanced for all treatments. Carry-over effects may occur but are unlikely when interventions are maintained for a longer period. Studies suggest that three weeks is needed for ApoA-I and HDL to rise to a maximum as well as their functionalities, such as paraoxonase activity and reverse cholesterol transport (Sierksma et al., 2002). Therefore, a selection of nutrition interventions of sufficiently long intervention duration may have provided more consistent and convincing results.

Overall, and unfortunately, classification of all pooled results as ´low´ or ´very low´ quality does not add to the consensus on the mechanisms that may or may not be involved in the moderate alcohol consumption-CVD association.

Specific Comments from Forum Members

Forum member Ellison considers that “It is reassuring that the limited number of human clinical trials that could be included in the present meta-analysis confirm a strong association between alcohol consumption and lipid factors that relate to the risk of cardiovascular disease. As stated, since similar lipid are seen for consumers of all types of alcoholic beverages (i.e., beer, wine and spirits), they likely relate to the alcohol content in these drinks.

Not evaluated in this meta-analysis is whether specific types of beverages, especially wine, may also have other mechanisms that affect risk. Most previous observational studies, as well as both animal and human experiments, have shown that the polyphenolic compounds in wine, in addition to its alcohol content, are associated with other metabolic factors that reduce the risk of such diseases.

Clinical trials in humans strengthen the consistent findings of almost all prospective epidemiologic studies based on self-report of alcohol intake that show lower risk of cardiovascular diseases among moderate drinkers than among similar people who are lifetime abstainers. Since the present paper is based on results of clinical trials, we do not have to worry about ‘under-reporting’ or other misclassification of alcohol exposure that may occur when estimates are based only on self-reported consumption.”

Forum member Skovenborg comments on the non-significant increase in Apo AI levels in females: MD: 7.31 mg/dl, 95% CI -0.67 mg/dl, 15,30 mg/dl. “The P value can be viewed as a continuous measure of the compatibility between the data and the entire model used to compute it, ranging from 0 for complete incompatibility to 1 for perfect compatibility, and in this sense may be viewed as measuring the fit of the model to the data. Too often, however, the P value is degraded into a dichotomy in which results are declared ‘‘statistically significant’’ if P falls on or below a cut-off (usually 0.05) and declared ‘‘nonsignificant’’ otherwise. (Greenland et al., 2016 ). Any particular threshold is arbitrary and the dichotomization into significant and non-significant results encourages the dismissal of observed differences. To the naked eye it is obvious that there is no real difference between the results of males and females.”

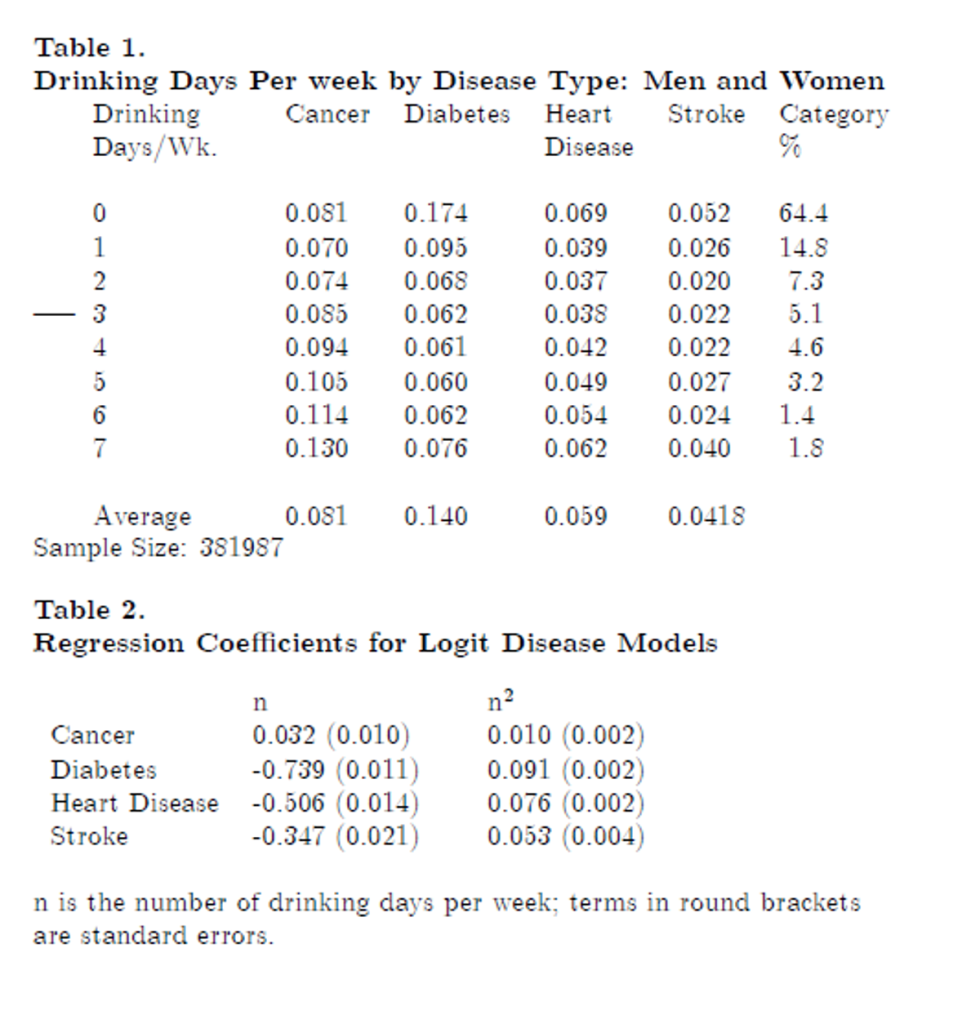

Forum member McIntosh considers that “Tables 1 and 2 (below) demonstrate the prophylactic effect of alcohol use on the four most prominent causes of death. Except for cancer, diabetes, coronary artery disease and stroke all respond positively up to 3 or 4 drinking days per week. This data comes from the 2022 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). These are based on the responses to questions such as “have you been told that you had melanoma or any other types of cancer?” The downward non-linear trajectory of prevalence rates as the frequency of drinking increases is confirmed by the quadratic functional representation in the Logit probability models, except cancer, which shows higher probabilities of occurrence as respondents drink more often. For the other three diseases, alcohol is beneficial at lower consumption frequencies but becomes harmful at higher frequencies[1] .

One of the interesting features of these results is that diabetes, coronary artery disease and stroke respond similarly to the frequency of alcohol consumption but have different physiological profiles. Hence, the study here is interesting because it sheds light on the mechanisms that cause alcohol use to reduce the likelihood of getting them. At a time when many researchers and public institutions are making claims which deny or diminish the importance of alcohol use as a prophylactic in combating these diseases, it is important to be able to understand why these diseases are so prevalent. Prominent studies that fall into this category are Wood et al., (2018), Zhao et al., (2024), and some of the institutional policy documents like the Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addiction Guidelines (2024) and the US Surgeon General’s (2024) document about excessive alcohol use and cancer. Many of the academic studies get results which support the position that small amounts of alcohol or none lead to the lowest risk of cancer. Most of these studies employ covariates in their models, which are correlated with alcohol use so that the true effect of alcohol use on heart disease or diabetes is understated, a result shown in Hendriks, McIntosh, and Stockley (2025). The studies considered in the meta-analysis reviewed here either do not use covariates that are correlated with alcohol use or their impact is small so that the relation between alcohol use and the apolipoprotein contained in HDL-cholesterol is unlikely to be compromised. The effects on diseases of these two compounds are likely to be substantial and highly correlated, so this is a major contribution in the war against the anti-alcohol lobby.

So why does alcohol use reduce the probability of getting coronary artery disease and stroke? Many studies show that the mechanism involves the effect of alcohol use on HDL-cholesterol. Klatsky (2015, p. 243), for example, notes that ” alcohol use increases HDL-cholesterol and this removes harmful lipids from blood vessel walls; a long-term effect; and is also a possible antioxidant and lowers risk of type II diabetes mellitus possibly by reducing insulin resistance.” Apolipoprotein is a major component in HDL-cholesterol, and it is thought to speed up the transfer of these harmful lipids to the liver, where they are excreted. Higher HDL cholesterol also reduces the probability of diabetes, but the mechanism is different. Higher HDL-cholesterol together with lower levels of triglycerides reduces insulin resistance (Yuge et al., 2023). Hence, HDL-cholesterol plays a major role in determining the probabilities of having cardiovascular disease or diabetes, possibly for different reasons. How this relates to the relative role that the constituent protein of HDL-cholesterol, apolipoprotein, plays in reducing disease probabilities is an interesting question which deserves further research.”

References

Baer, D. J., Judd, J. T., Clevidence, B. A., Muesing, R. A., Campbell, W. S., Brown, E. D., & Taylor, P. R. (2002). Moderate alcohol consumption lowers risk factors for cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women fed a controlled diet. Am J Clin Nutr, 75(3), 593–599.

Branchi, A., Rovellini, A., Tomella, C., Sciariada, L., Torri, A., Molgora, M., Sommariva, D. (1997) Association of alcohol consumption with HDL subpopulations defined by apolipoprotein A-I and apolipoprotein A-II content. Eur J Clin Nutr, 51(6), 362-5.

Brien, S. E., Ronksley, P. E., Turner, B. J., Mukamal, K. J., & Ghali, W. A. (2011). Effect of alcohol consumption on biological markers associated with risk of coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies. BMJ, 342, d636. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d636

Chambless, L.E., Heiss, G., Folsom, A.R., Rosamond, W., Szklo, M., Sharrett, A.R., & Clegg, L.X. (1997) Association of coronary heart disease incidence with carotid arterial wall thickness and major risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, 1987-1993. Am J Epidemiol, 146(6), 483-94.

Clevidence, B. A., Reichman, M. E., Judd, J. T., Muesing, R. A., Schatzkin, A., Schaefer, E. J., Li, Z., Jenner, J., Brown, C. C., & Sunkin, M. (1995). Effects of Alcohol Consumption on Lipoproteins of Premenopausal Women: A Controlled Diet Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 15(2), 179–184.

de Jong, H.J., de Goede, J., Oude Griep, L.M., & Geleijnse, J.M. (2008) Alcohol consumption and blood lipids in elderly coronary patients. Metabolism, 57(9), 1286-92.

Ding, C., O’Neill, D., Bell, S., Stamatakis, E., & Britton, A. (2021). Association of alcohol consumption with morbidity and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease: original data and meta-analysis of 48,423 men and women. BMC Medicine, 19(1), 167. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02040-2

Durrington, P.N. (1993) How HDL protects against atheroma. Lancet, 342, 1315-6.

El Khoudary, S. R., Aggarwal, B., Beckie, T. M., Hodis, H. N., Johnson, A. E., Langer, R. D., Limacher, M. C., Manson, J. E., Stefanick, M. L., & Allison, M. A. (2020). Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: Implications for timing of early prevention: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 142(25), e506–e532. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000912

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. (2020). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (London, England), 396(10258), 1204–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

Hendriks, H. F. J. (2020). Alcohol and human health: What is the evidence? Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 11(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-food-032519-051827

Hendriks, H.F.J., McIntosh, J., & Stockley C.S. (2025) Alcohol, mortality and health. Unpublished manuscript.

Hines, L.M., & Rimm, E.B. (2001) Moderate alcohol consumption and coronary heart disease: a review. Postgrad Med J, 77(914), 747-52.

Huang, Y., Li, Y., Zheng, S., Yang, X., Wang, T., & Zeng, J. (2017). Moderate alcohol consumption and atherosclerosis: Meta-analysis of effects on lipids and inflammation. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 129(21–22), 835–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-017-1235-6

Khatiwada, A., Christensen, S. H., Rawal, A., Dragsted, L. O., Berg-Beckhoff, G., & Wilkens, T. L. (2025). Effect of moderate alcohol intake on blood apolipoproteins concentrations: A meta-analysis of human intervention studies. Nutr Metab Cardio Dis: NMCD, 103854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2025.103854

Klatsky, A.L. (2015) Alcohol and cardiovascular diseases: where do we stand today?.” J Int Med, 278(3), 238-250.

Klatsky, A.L., & Udaltsova, N. (2007). Alcohol drinking and total mortality risk. Ann. Epidemiol., 17(5, Supplement 1): S63-S67.

Klimov, A.N., Gurevich, V.S., Nikiforova, A.A., Shatilina, L.V., Kuzmin, A.A., Plavinsky, S.L., & Teryukova, N.P. (1993) Antioxidative activity of high density lipoproteins in vivo. Atherosclerosis, 100(1): 13-8.

Li, X., Hur, J., Smith-Warner, S.A., & Song, M. (2025) Alcohol intake, drinking pattern, and risk of Type 2 diabetes in three prospective cohorts of US women and men. Diabetes Care, dc241902.

Mackness, M.I., Abbott, C., Arrol, S. & Durrington, P.N. (1993) The role of high-density lipoprotein and lipid-soluble antioxidant vitamins in inhibiting low-density lipoprotein oxidation. Biochem. J. 294, 829-34.

Magnussen, C., Ojeda, F. M., Leong, D. P., Alegre-Diaz, J., Amouyel, P., Aviles-Santa, L., De Bacquer, D., Ballantyne, C. M., Bernabé-Ortiz, A., Bobak, M., Brenner, H., Carrillo-Larco, R. M., de Lemos, J., Dobson, A., Dörr, M., Donfrancesco, C., Drygas, W., Dullaart, R. P., Engström, G.,… & Blankenberg, S. (2023). Global effect of modifiable risk factors on cardiovascular disease and mortality. New Eng J Medi, 389(14), 1273–1285. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2206916

Mathews, M. J., Liebenberg, L., & Mathews, E. H. (2015). The mechanism by which moderate alcohol consumption influences coronary heart disease. Nutri J, 14(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-015-0011-6

Mukamal, K. J., Chiuve, S. E., & Rimm, E. B. (2006). Alcohol consumption and risk for coronary heart disease in men with healthy lifestyles. Arch Intern Med, 166(19), 2145–2150. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.19.2145

Mukamal, K. J., Jensen, M. K., Grønbæk, M., Stampfer, M. J., Manson, J. E., Pischon, T., & Rimm, E. B. (2005). Drinking frequency, mediating biomarkers, and risk of myocardial infarction in women and men. Circulation, 112(10), 1406–1413. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537704

Paradis, C., Butt, P., Shield, K., Poole, N., Wells, S., Naimi, T., Sherk, A., & the Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines Scientific Expert Panels. (2023). Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report. Ottawa, Ont.: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.

Parker, D.R., McPhillips, J.B., Derby, C.A., Gans, K.M., Lasater, T.M., & Carleton, R.A. (1996) High-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and types of alcoholic beverages consumed among men and women. Am J Public Health, 86(7), 1022-7.

Ruidavets, J.B., Ducimetière, P., Arveiler, D., Amouyel, P., Bingham, A., Wagner, A., Cottel, D., Perret, B., & Ferrières, J. (2002) Types of alcoholic beverages and blood lipids in a French population. J Epidemiol Community Health, 56(1), 24-8.

Rimm, E.B., Klatsky, A., Grobbee, D., & Stampfer, M.J. (1996) Review of moderate alcohol consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: is the effect due to beer, wine or spirits? Br Med J, 312,731–6.

Rimm, E. B., Williams, P., Fosher, K., Criqui, M., & Stampfer, M. J. (1999). Moderate alcohol intake and lower risk of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of effects on lipids and haemostatic factors. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 319(7224), 1523–1528. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7224.1523

Rosales, C., Gillard, B. K., Gotto, A. M. J., & Pownall, H. J. (2020). The alcohol-high-density lipoprotein athero-protective axis. Biomolecules, 10(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10070987

Sierksma, A., Van Der Gaag, M. S., Van Tol, A., James, R. W., & Hendriks, H. F. J. (2002). Kinetics of HDL cholesterol and paraoxonase activity in moderate alcohol consumers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 26(9), 1430–1435. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000374-200209000-00017

Spaggiari, G., Cignarelli, A., Sansone, A., Baldi, M., & Santi, D. (2020). To beer or not to beer: A meta-analysis of the effects of beer consumption on cardiovascular health. PloS One, 15(6), e0233619. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233619

Stoekenbroek, R. M., Stroes, E. S., & Hovingh, G. K. (2015). ApoA-I mimetics. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 224, 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09665-0_21

U.S. Surgeon General (2024). Alcohol and Cancer Risk.

Wilkens, T. L., Tranæs, K., Eriksen, J. N., & Dragsted, L. O. (2022). Moderate alcohol consumption and lipoprotein subfractions: a systematic review of intervention and observational studies. Nutr Rev, 80(5), 1311–1339. https://doi.org/10.1093/NUTRIT/NUAB102

Wood AM, Kaptoge S, Butterworth AS, Willeit P, Warnakula S, Bolton T, Paige E, … Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration/EPIC-CVD/UK Biobank Alcohol Study Group. (2018) Risk thresholds for alcohol consumption: combined analysis of individual-participant data for 599 912 current drinkers in 83 prospective studies. Lancet, 391(10129), 1513-1523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30134-X. Erratum in: Lancet. 2018 Jun 2;391(10136):2212. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31168-1. PMID: 29676281; PMCID: PMC5899998.

Wu, B., Fan, B., Qu, Y., Li, C., Chen, J., Liu, Y., Wang, J., Zhang, T., & Chen, Y. (2023). Trajectories of blood lipids profile in midlife women: Does menopause matter? J Am Heart Assoc, 12(22), e030388. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.030388

Yuge, H., Okada, H., Hamaguchi, M., Kurogi, K., Murata, H., Ito, M., & Fukui, M. (2023) Triglycerides/HDL cholesterol ratio and type 2 diabetes incidence: Panasonic Cohort Study 10. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 22(1), 308. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02046-5.

Zhang, Y.-B., Pan, X.-F., Chen, J., Cao, A., Xia, L., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Li, H., Liu, G., & Pan, A. (2021). Combined lifestyle factors, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Epidemiol Community Health, 75(1), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214050

Zhao, J., Stockwell, T., Naimi, T., Churchill, S., Clay, J., & Sherk, A. (2023) Association between daily alcohol intake and risk of all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analyses. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Mar 1;6(3):e236185. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.6185. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2023 May 1;6(5):e2315283. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.15283.

Comments on this critique by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research were provided by the following members:

Henk Hendriks, PhD, Netherlands

Creina Stockley, PhD, MBA, Independent consultant and Adjunct Senior Lecturer in the School of Agriculture, Food and Wine at the University of Adelaide, Australia

R. Curtis Ellison, MD, Section of Preventive Medicine/Epidemiology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA

Richard Harding, PhD, Formerly Head of Consumer Choice, Food Standards and Special Projects Division, Food Standards Agency, UK

Erik Skovenborg, MD, specialized in family medicine, member of the Scandinavian Medical Alcohol Board, Aarhus, Denmark James McIntosh, PhD, Retired Professor of Economics, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada

[1] Frequencies are used instead of the number of the BRFSS data on drinks per day is not as reliable as frequency data. It is also reasonable to assume that recall errors will be smaller for frequencies than actual drinks consumed. The results here are very similar to the recent study by Li, Hur, and Smith-Warner (2025).

Proudly powered by WordPress. Theme by Infigo Software.